Who was the Howling Mob Society?

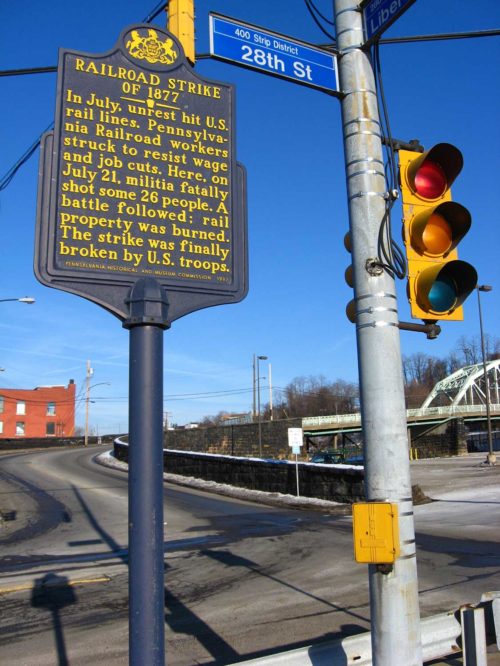

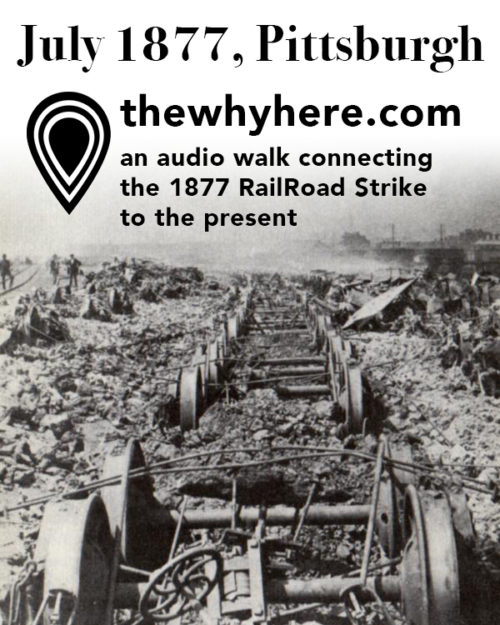

The Howling Mob Society was a Pittsburgh-based group of anonymous artists, activists, and citizen historians with an interest in the oft-buried radical peoples’ history of the United States. We worked as a team throughout 2007-08 to research, fabricate, and install a series of ten historical markers which detail the events of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 as they unfolded in Pittsburgh, PA.

In 2008, The Howling Mob Society received an Acknowledgment Award from the Pittsburgh Creativity Project at Carnegie Mellon University.

In 2012, our work was featured in the U.S. Pavilion at the 13th International Architecture Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia, Italy.

The Howling Mob Society has been featured in several publications, including Gregory Sholette’s Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture (Pluto Press, 2011) and a feature by Nicolas Lampert (author of A People’s Art History of the United States, The New Press, 2013) in Proximity magazine, issue #003 Fall/Winter 2008, which you can read here. The entire marker series is listed in the Historical Marker Database online, which includes their mobile app.

“The Mob”, as we called ourselves, unofficially disbanded around 2010.

As of 2020, four of these original ten historical markers are still standing in public.

What do you mean by calling yourselves a “howling mob”?

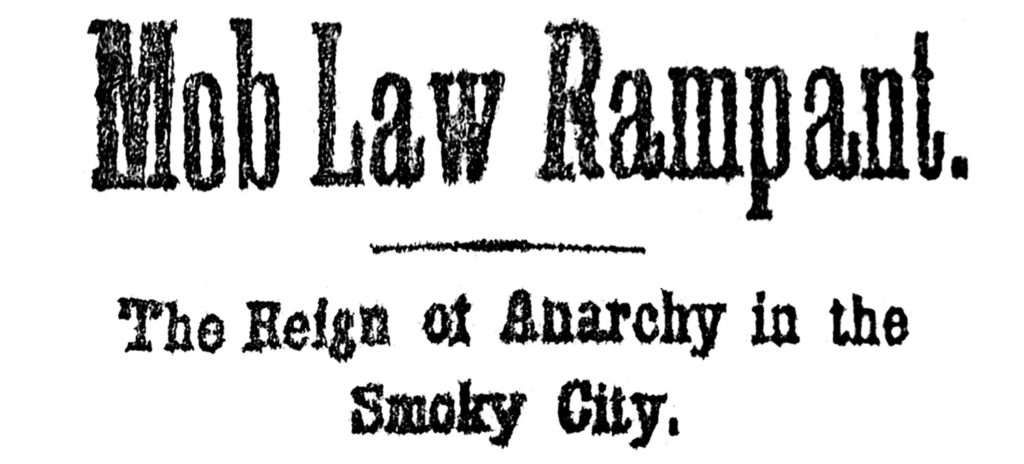

The origin of the term “howling mob” as we use it comes from an article in Harper’s Weekly, published in the aftermath of the Railroad Strike on August 11, 1877. Illustrating a popular working-class insurrection as a terrifying nightmare (which, to the ruling class, it was), they wrote: “The sixth and seventh days of the revolution, July 21 and 22, were the darkest and bloodiest of all. The city of Pittsburgh was completely controlled by a howling mob, whose deeds of violence were written in fire and blood.” Such overwrought language was commonplace in the media surrounding these events in their day.

Why focus on the Railroad Strike of 1877?

The Railroad Strike of 1877 was not a strike alone, and the title itself is less than accurate. Although the insurrection was rooted in the grievances of railroad workers in the Eastern United States, it was by no means limited to the railroad industry. This was not a clearly announced action or strike. It was not originally condoned by any union or political organization. The actions from railroad workers were met with immediate support from coal miners and other industrial workers who saw a clear distinction between themselves and the wealthy magnates they labored under. Workers struck in solidarity across trades, and these frustrations were not limited to the largely male workforce: railroad companies were carving up the land as well as the interior of major cities across the country. Often driving straight through the middle of major pedestrian areas, the railroad disrupted and endangered the lives of the women and children as well. Railroad companies were the first major corporations in America, and they operated largely above the law – the events of 1877 were a broad-based and spontaneous attack against the largest industrial monopolies of the time, and the wealth and power that they wielded. Some historians consider these events to have been the first mass anti-corporate protest in the history of the United States.

It can not be ignored that in most cities where the events of 1877 spread, full-scale riots erupted, often resulting in injuries and deaths, although the documented majority of these were at the hands of law-enforcement officials and ad-hoc vigilante mobs in the employ of city governors. We are not suggesting the celebration of a riot so much as we are hoping to elaborate on the conditions which led to it, and to comment on the role private property plays in our capitalist society. Many historians have avoided the story of the Strike, since it is difficult to point to stated grievances, motivations, figureheads and leaders. Many accounts of the events end up focusing only on the scale of the property destruction that occurred, paying little attention to the conditions leading up to the strike or the desperation and exhilaration people must have felt as the situation unfolded.

Frustrated by the “official” accounts, and the lack of local understanding of a massive event which took hold of our hometown +140 years ago, we came together to tell the story with a focus on the working class people whose voices are rarely heard.

What happened after the Strike? Was it successful?

It is difficult to define success in terms of the events of 1877, since the “strike” itself was really a general uprising against a veritable laundry list of modern ills. In many ways the insurrection was a significant milestone within the labor movement, particularly as it helped to illustrate a potential for worker solidarity which spanned industries, and the power those workers could wield collectively.

In the immediate aftermath, most of the major railroad lines rescinded the particular pay cuts which had sparked much of the striking activity in the spring and summer of 1877, as it became apparent that continued wage cuts would be impossible: the collective fury of their workers would simply not allow a further slide into poverty. The general consensus seemed to be that settling the specific wage disputes in the short run would at least ensure that more property was not destroyed and lines continued to run as scheduled. Many workers who were identified as having participated in property destruction were not hired back into the railroad. Socialist and Communist currents stirred louder in the Strike’s aftermath. Many also saw the great lesson of 1877 as a need for formalized leadership within trade unions. Meanwhile, major cities decided on the value of beefing up their local militias and fortifying their armories to deflect future uprisings. President Rutherford B. Hayes went down on record for having been the first to use federal troops to quell a labor dispute.

As for Pittsburgh, most of the area between Grant Street and 33rd Street was completely destroyed by fire. Here, the insurrection largely burned itself out as rioters ran out of energy and targets, and looters took home most everything that could be carried off of the stopped trains. As the National Guard rolled into the city, they found that the riots had mostly settled. A volunteer force of about 300 armed citizens, organized by the mayor, patrolled the city for the next week, but saw little action. Other wage strikes subsequently erupted in surrounding towns such as McKeesport and Braddock, where parading was often successful in achieving settlements, and disturbances never reached the fever pitch of Pittsburgh.

Although Allegheny County eventually paid the Pennsylvania Railroad Company $1,400,000 plus interest for damages to their property during the strike, Thomas Scott himself, president of the PRR, was ruined. His venture of laying the new Texas Pacific rail line was dead, and he sold the PRR to John D. Rockefeller in October of 1877. He died four years later.

Why make historical markers?

We believe that a series of public markers would go a long way towards telling the story of 1877 in an accessible and public format. The “official” language of historical plaques and other forms of public display can often be curious and troubling, as the tendency is to oversimplify the situation at hand and omit key contextual details. It can be a tricky balance between telling as much of the story as you can, and holding a viewer’s attention. We hope that we have accomplished both.

How do these events from 1877 relate to our lives now?

As in 1877, the stories of many contemporary protests and other public actions are often told by corporate-owned media outlets whose role is to destabilize and marginalize challenges to power in this country and others. In our research, we found that the mainstream newspapers of the time often reacted to the events then as they might now – blatantly dodging the root issues of working class people by focusing on the more sensational angles and the role of property. Many newspaper accounts of the strike were predictably critical of the motivations behind these events, often relying on racist and xenophobic language to parlay blame from the wealthy corporations with a vested interest in these same publications. Looters were demonized as opportunistic criminals, the power of the military and the law was celebrated. Careful language was used to obfuscate the true nature of the strikes and the state-sponsored violence that turned a rebellious gathering based on legitimate grievances into a full-scale riot.

How do I find out more about the Strike?

Accounts of these events which were published at that time are largely one-sided and critical of the motivations behind this popular rebellion, even though thousands of citizens in dozens of cities participated in and/or supported them. Determining specific facts became difficult, as accounts vary from paper to paper. It is also important to note that these histories, as we find them, are rarely written by the people who participated in them – if they were, they were not published and archived. This goes a long way towards illustrating how we have come to know the events of 1877, as well as countless other struggles for social justice in this country’s history. Most of the details as they have been remembered were set to print by newspapers whose opinions were guided by the men who owned them – often invested in the same futures that the railroad owners were. Although there is some record of supportive press about the strike in the publications of the trade unions of the time, they are difficult to find and reference. Howard Bruce’s book, 1877: Year of Violence goes a long way towards piecing the story together from the available journals of the period. This book and others are listed in our bibliography.