The Great Strike of 1877 and the uprising that ensued did not begin in Pittsburgh, and it did not start on the Pennsylvania Railroad. The grievances of brakemen employed on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad first led to a strike in Baltimore, Maryland on July 16th. The next day, trainmen in Martinsburg, West Virginia also went on strike. Unrest quickly spread throughout the country—beyond the B&O and beyond the railroad industry at large.

The Great Strike was a spontaneous and chaotic action, independent of unions and political organizations. When the outrage took hold in Pittsburgh, it ignited a popular uprising of working men, their families and neighbors alike. Common citizens stopped train services, burned railroad property and looted freight cars. It was an anti-corporate gesture of unimaginable proportions. The events of 1877 marked the first time that the National Guard was called upon to defend privately-owned property against an unsympathetic populace. As a result, The Great Railroad Strike set a precedent for state aggression against subsequent labor movements.

In the lead up to the strike, a downturn in the national economy coupled with over-speculation in the railroad industry caused declining profits for railroad owners. In order to compensate, these owners cut the wages of brakemen by ten percent: only one in a long line of new wage cuts. Railroad owners squeezed their employees to the very limit—-maximizing their profits while laborers toiled in increasingly dismal and glaringly dangerous working conditions. The trains themselves were not only dangerous for those working on them; in 1868 in New York state alone, 150 people were killed and 86 were injured by trains. Many of these deaths and injuries included non-employees and non-passengers.

Even accounting for recession and over-speculation, lost profits in the railroad industry were largely exaggerated. By 1877, Thomas Scott himself pulled in $175,000 per year, while an average worker on his railroad earned less than $400 in the same period, working 72 hour weeks. Massive layoffs led to a 27% unemployment rate, while those left on the job were forced to compensate with longer hours and more strenuous labor. Poverty, ill health, exploitation and debt plagued the lives of working people and their families. Workers and community members throughout the country were pushed to the point of desperation and destitution. In July of 1877, they rose up, without central organization or clear leadership, to attack the monopolies responsible for their economic condition.

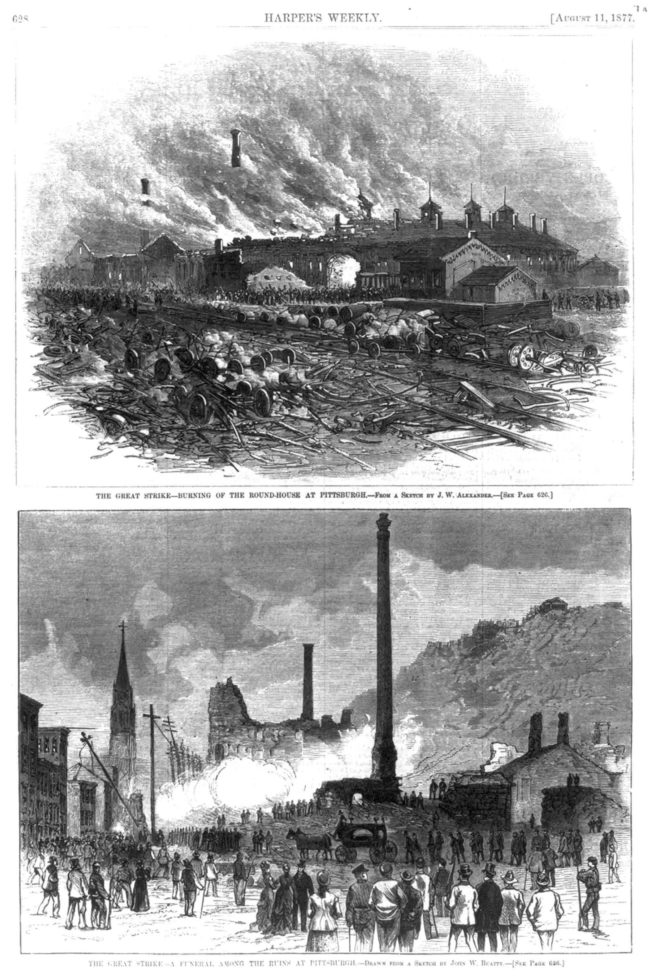

The sixth and seventh days of the revolution, July 21 and 22, were the darkest and bloodiest of all. The city of Pittsburgh was completely controlled by a howling mob, whose deeds of violence were written in fire and blood.

- Harpers Weekly, August 1, 1877

The events that unfolded in July of 1877 marked a unique moment in the history of the United States. Exceptional as it was, however, what has come to be known as the Great Railroad Strike goes largely unmentioned in mainstream accounts of Pittsburgh history. Common people were pushed to the breaking point and struck out in resistance, however they did not have the opportunity to preserve their stories for posterity. Those who had the means to record the strike quickly revealed their sympathetic relationship to the business leaders of the day and set the tone for how 1877 would be remembered. Their bias can be seen in published accounts of the riots, which use racist and xenophobic language to blame immigrants and transient laborers for the property damage and looting that took place. Considerably less attention is paid to the conditions that incited the riot in the first place; the fact that in Pittsburgh alone one quarter of the city’s population participated in the uprising; or the lives lost at the hands of the state militia and National Guard.

In a culture that tells its history through the stories of great men and war heroes, a movement without iconic leaders quietly falls to the wayside. Telling the story of a decentralized social insurrection requires a different approach to history making. It requires that individuals outside the traditional power structure stand up and take responsibility for setting the record straight. This is where we began our work.